The Germans Of North Harris

County, Texas

BY

John T. Payne

Presented to the

Raleigh Tavern Philosophical

Society

December 2, 2004

Prologue

Every day, as we rush about from here to there, we are constantly

surrounded by hundreds, yes, even thousands of names. The community where we

live, the street where our house is located, the businesses in the area, all of

these, and many more whirl by us at alarming speed, and we rarely take the time

to think about them. This is even more the case if we do not live in the same

area as our birth but rather drop into a place as adults and have not grown up

with stories of the area.

This is my situation having moved to

Tomball, TX only five years ago after a lifetime of traveling around the world

with no particular roots but with a strong interest in history. Even as my wife

and I were looking for a place to live in the area, I was aware that many of

the names around me in the Tomball area were not of Anglo-Saxon origin, for

instance, Juergen Road, Mueske Road, Buvenhausen Street and Burkhardt Street.

As we began the construction of our home, my interest was further peeked by the

names of those who came to complete the work: Schneider, Scholl, and Strack and

many more.

My interest in history, coupled with

my interest in the names that continued to pop up, pushed me into researching

the origins of all these names. From where did they come? When? Why? This is

the story I hope to tell in this very short paper.

The Discovery of Texas: The First Immigrants

The

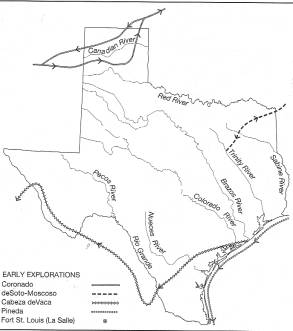

Spanish were the first Europeans to “discover” Texas. In1519 Alonzo Alvarez de

Pineda mapped the coast of the Gulf of Mexico from Florida to Vera Cruz. Pineda

observed the Texas coast during his voyage but made no significant comments

about the area.

Alvar Nunez Cabeza de Vaca was the

first European to spend time in Texas and to describe what he saw. In 1528, he

and three companions were survivors of a

shipwreck on a small island near present day Galveston (Harris county).

The party was captured by the natives in the area and held as prisoners for six

years before they eventually escaped and made their way back to Mexico. They

wandered through a great deal of South Texas and northern Mexico before

arriving at a Spanish outpost near the Gulf of California in western Mexico in

1536. (See fig. 1)

Upon his return, Cabeza de Vaca

related stories heard from his Indian captors of large cities in the north

where gold and silver were abundant. In 1540 Francisco Vasquez de Coronado came

looking for the riches with no success. Coronado was followed in 1542 by

Hernando de Soto who was equally unsuccessful in discovering riches in the

frontier regions of New Spain.

Although no riches were discovered,

these explorations strengthened Spanish claims to present- day Texas. They also

tended to discourage Spanish interest in the area since there was no gold or

silver to be had and the natives were hostile to the foreign intruders.

It was the French who prompted the

Spanish to pay more attention to Texas. In 1682 Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La

Salle left Quebec and explored the entire Mississippi River claiming the entire

river basin for France. In 1684 La Salle received a commission from the King to

establish a colony at the mouth of the Mississippi River. Navigation being what

it was in those days, La Salle missed the mouth of the river and landed at

Matagorda Bay on the Texas coast in February 1685. He erected a crude stockade,

Fort St. Louis, and began exploring the countryside. Eventually La Salle was

killed by his own men and Fort St. Louis was destroyed.

Fig. 1 (24, P.23)

Responding to the French provocation

to what they considered their territory, the Spanish, in 1689, sent an

expedition under Alonso de Leon to remove the threat only to find that the

Indians had done the work for them. Upon returning to Mexico, de Leon

recommended Spain should occupy the area at once. This led to the establishment, in late 1690, of the first of many

Spanish missions in Texas, San Francisco de los Tejas, near the present-day

village of Weches in Houston County.

The history of the Spanish Missions

in Texas, especially east Texas, from 1690 to 1763 is colorful and fascinating

and usually driven by the fear of French encroachment on what the Spanish

considered their territory. If the French threat seemed to be high, Spanish

Missions received much attention and if the threat seemed low, the missions

received little attention. It was the end of the French and Indian War and the

resulting 1763 Treaty of Paris that significantly changed the situation.

The 1763 Treaty of Paris, which

pushed France off the North American continent, left Spain in possession of

Louisiana. With France no longer a threat the Spanish concluded that their

far-flung outposts need no longer be maintained and a royal order was issued

leading to the abandonment, in 1772, of all settlements in Texas except San

Antonio and La Bahia (Goliad). Except for isolated instances, east Texas was to

remain virtually empty of European influence until after the turn of the

nineteenth century.

Early Colonization Ideas

In 1800, Napoleon of France forced

Spain to return Louisiana, and in 1803,

he sold the territory to the United States. Now Spain was faced with a new

threat - those land hungry Americans. In light of this threat, Spain adopted a

threefold imperial policy: (1) hold the territory with its ancient boundaries

in place; (2) increase its garrisons and colonize the territory with loyal

Spanish subjects; (3) keep the Anglo-American intruders out.

The western border of the Louisiana

Purchase was ill defined at best. The United States believed the border to be

the Rio Grande River while the Spanish believed it to be the Red River a

difference of several hundred miles. This situation was not resolved until the

conclusion of the Adams-Onis treaty in 1819 in which the western boundary of

the Louisiana purchase was finally fixed.

In the late eighteenth and early

nineteenth century a few people, some of German parentage, began to make their

way to Texas from the United States. Most of these immigrants, known as

Anglo-Americans, were from the southern states. Spanish official policy frowned

on these settlers, but Spanish presence in the area was so sparse there was

little they could do about it. Even as late as 1820 the total population of

Texas was less than 3,000 and most of the Spanish were concentrated in San

Antonio de Bexar and Bahia (Goliad).

Early in the nineteenth century the

Spanish were looking for ways to counter expansion into their frontier area by

introducing immigrants from other nations to populate the northeastern

frontier. The earliest proposal for settling Germans in Texas was made by

Morphi, the Spanish consul at New Orleans. In 1812 the consul proposed to the

Spanish government that German and Polish soldiers be sent to Texas to serve as

a buffer against Napoleonic aggressions in Texas. Morphi wanted to detach

German and Polish soldiers in Napoleon’s army from their allegiance to France

and induce them to settle in Texas, “where they could devote themselves to

agriculture and the useful arts, thus securing their own happiness and the

welfare of the province. He wished to grant them seven square leagues of land (a

league is 4,428 acres) along the Gulf of Mexico near the Louisiana frontier, to

exempt them from taxation, to allow them free trade with all nations, and to

invest them with local authority. Only artisans and mechanics of good character

were to be introduced.” (1, P. 21).

Despite the Spanish need to populate the frontier this plan was not

approved for fear it would introduce a fifth column into the territory, which

could revolt and deliver the area to France.

In 1814, Don Ricadro Reynal Keene, a

member of the Spanish court, made a proposal to the King for placing foreign

settlers in Texas. He proposed that both Irish and Germans be brought to Texas

because they could aid in building up the agriculture and commerce of the

province and protect the frontier of New Spain. Keene received a grant for this

settlement, but the conditions required two-thirds of the settlers should be

Spaniards while others might come from any foreign country except France. Keene

was never able to recruit enough Spaniards to fulfill these conditions and the

grant expired. (14, P. 241)

In the spring of 1819, a group of

Swiss citizens living in Philadelphia proposed to Don Louis de Onis, Spanish

Minister to the United States, the establishment of a colony of Swiss and

Germans on the Trinity River in Texas. They later modified the request to

include locations on the Sabine, the San Antonio or the Guadalupe Rivers

instead of the Trinity. These colonists were to produce agricultural products

for Spain and also help protect the frontiers of Texas against the enemies of

Spain. Action on this request was delayed while the King of Spain was making up

his mind on the Florida Treaty (Adams-Onis), which was being negotiated with

the United States. This plan was overcome by events when Mexico obtained its

independence. (1, P. 22).

By 1820, the Spanish Cortez (ruling

council) was getting desperate to stem the tide of intrusions by American

filibusters and so issued a decree opening all Spanish dominions to any

foreigners who would respect the constitution and laws of the monarch. Thus was

instituted the empresario system in which contracts were made with

certain individuals (empresarios) which called for the settlement of specified

numbers of immigrants in tracts of land granted to the empresario by the

government. The first contract was made with Moses Austin, an American who had

acquired Spanish citizenship during an earlier residence in Missouri. At his

death, the contract passed to his son, Stephen F. Austin, the man who has been

called the “Father of Texas.”

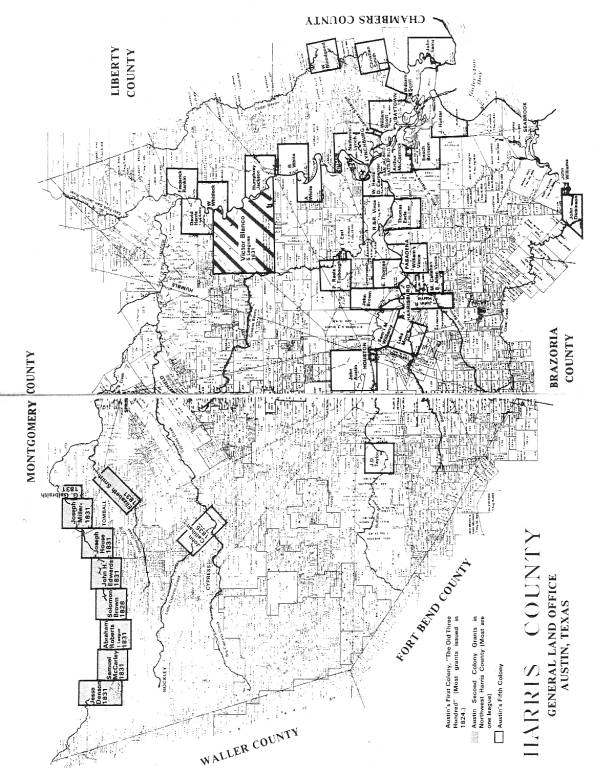

Austin’s colony lay in south-central

Texas, between the Colorado and San Jacinto Rivers (Fig. 2) Settlement began in

the early 1820’s. Settlers arrived in the colony both overland through

Louisiana and Arkansas and by sea from the ports on the Gulf principally New

Orleans. Eventually Austin received three additional grants for colonies in

Texas and all proved to be very successful.

Fig.2 (7, P. 16)

Fig.2 (7, P. 16)

The German Connection

In the broadest sense of the word North

America has been the goal of German emigration for over 300 years. The first

German settlement here was Deutschstadt (present-day Germantown, PA) in

1683. For the most part, religious freedom served as the emigration motivation

in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. In the nineteenth century the

drivers for emigration were political and economic.

Following the Napoleonic Wars and

the Congress of Vienna in 1815, the reaction against liberal tendencies caused

many to seek political freedom. During the early nineteenth century,

particularly in the early thirties and in the revolutionary period of 1848 to

1849, the desire for political improvement served as the outstanding motive for

emigration. When the revolutionary movements of these years failed, many

Germans were forced to flee from their native land in order to escape military

punishment.

During this period the average

German was no better off economically than politically. The industrial life of

the Rhine region left many people very poor and a few very rich. Farmers were

no better off than industrial workers because they followed the method of

dividing farms equally among all sons in a family (Roman law) in many of the German states. Farms

continually shrank in size, and they could no longer support families. To add

to the farmers’ problems the potato blight was spreading from Ireland. This was

followed by poor cereal harvests resulting in famine in many cases.

In a book published in 1821, a

retired Prussian army officer proposed perhaps the most ambitious plan for

German colonization in Texas. In this book, J. Val Hecke, described his travels

in North America made in the years 1818 and 1819. He expressed his opinion of

the value of Texas as a Prussian colony. This was a time of growing nationalism

in Europe. He proposed buying the territory of Texas from Mexico to be turned

into a German colony. Hecke believed that buying the area of Texas should be

easy as the Mexican government had little interest in it. Hecke proposed that if the Prussian

government were unable to buy Texas then merchants should advance the money.

They could form a trading company like the British East India Company with the

government furnishing the troops for protection of the province. Hecke’s book

was widely read throughout the German states, but his plan proved to be

premature and so was never carried out. (1, p.23)

Another book published in Germany in

1829 is attributed by many as the vehicle which stirred many Germans to

emigrate to America. Gottfried Duden traveled to the United States in 1824 and

spent four years in Missouri. He wrote a report of his travels and experiences

in America. In the preface of his book, he stated that “most of the evils from

which the inhabitants of Europe, and particularly of Germany, suffer arise from

overpopulation and are of such a nature that all remedies remain without effect

unless a thinning out of the population precedes them” (1, P. 3) Duden believed

that the only practicable remedy for overpopulation was emigration. This book was

widely read throughout the southwestern part of Germany and struck a resonate

chord among the farming population which could no longer support itself.

Post Mexican Independence Situation

On 27 September 1821, the revolt of the Mexicans began in 1810 ended

with success and the Mexican nation came into being. However, the new Mexican

nation was very unstable with many competing factions making it difficult for

all concerned.

In November of 1821 the first

settlers to Austin’s first colony began arriving in Texas at Washington on the

Brazos. When Austin went to San Antonio to report his progress he learned of

Mexican independence, and for a while it appeared that the Mexican government

would not honor the contract given to Moses Austin by Spain. With the help of

Baron de Bastrop, Austin was able to gain recognition of his colony. For the

next few years Austin proved to be the most successful of all the empresarios

settling four separate grants bringing settlers to the previously sparsely

populated northern frontier of Mexico

In 1826, Joseph Vehlein, a wealthy

German merchant, received an empresario contract from Spain to establish

a colony near Galveston Bay of “three hundred industrious families,

professionals of the Catholic religion, and of good moral habits, part of them

to be Germans and Swiss and part of them from the States of North America.” (1,

P. 25) Somewhat later Vehlein received

a second contract for one hundred families in the same area with the requirement

that they be Germans, Swiss and English, that is all Europeans, no North

Americans.

By 1828 the Mexican government was

concerned with the rate of settlement on its frontier and sent General Manuel

Mier y Teran to investigate the situation. Officially the general’s mission was

to survey the eastern boundary defined in the Adams-Onis Treaty, but his real

mission was to see how the exploding American colonies were progressing. Upon

his return to Mexico City, the General reported alarm at the situation and said

Mexican influence diminished rapidly as he proceeded eastward. The

Anglo-Americans were taking over the country, and he concluded that Mexico must

act immediately or lose Texas.

General Mier y Teran made several

recommendations to the Mexican government for countering the growing Anglo presence

to the north. He proposed first that Mexican colonists be sent to the frontier

to dilute the Anglo influence. He further recommended Swiss and Germans be

recruited for colonies in the area. In order to draw Texas tighter to the

Mexican state, he proposed coastal trade between Texas and the rest of the

republic be expanded, and finally he proposed sending more Mexican troops to

the frontier to enforce Mexican law.

In 1830, Mexican President

Bustamonte put into law what General Mier y Teran had proposed with legislation

prohibiting the introduction of more immigrants from the United States into

Texas and suspended all contracts not already completed or not in harmony with

the law. The Austin and Dewitt colonies received an exception enabling them to complete

the settlement of their quotas of families. The law had further provisions for

expanding a Mexican military as well as civilian presence in the area. It was

this body of legislation, which set in motion the Texas independence movement

and opened the door for expanded non-U.S. immigration.

One result of Bustamonte’s sweeping legislation was

the creation of the Galveston Bay and Texas Land Company when Joseph Vehlein

joined with David Burnet and Lorenzo Zavala, who had adjoining contracts around

Galveston Bay, which also adjoined Austin’s colony. The express purpose of this

new company was the settlement of Europeans in Texas. The Galveston Bay and

Texas Land Company was the vehicle through which a few early German immigrants

arrived in Harris County.

In 1831, Friedrich Ernst, the man often referred to

as the “father of German immigration to Texas, arrived in Harrisburg (Houston).

Harrisburg, founded in1823 by John Richardson Harris at the junction of Buffalo

Bayou and Bray’s Bayou was a thriving port by 1831. Ernst was born at Varel in

the duchy of Oldenburg. In 1829 he became dissatisfied with conditions in

Germany, and he emigrated to America with his family.

It was after Ernst’s arrival in New York that he read

Duden’s book and decided to go to Missouri. Enroute to New Orleans a fellow

passenger gave Ernst a pamphlet containing a description of Texas. Ernst

changed his destination and landed in Harrisburg in April 1831. From Harrisburg

he traveled to San Felipe de Austin and received a league of land on the west

side of the west fork of Mill Creek.

Not long after his arrival in Texas, Ernst wrote a

long letter to an old friend in Oldenburg. His letter was published in an

Oldenburg newspaper. It was widely read and eventually reprinted in a book

published in 1834, which was among the earliest to appear in Germany about

Texas. In his letter Ernst described Texas in glowing terms. He described how a

married settler could obtain a league of land by paying only $160 for the

survey and the recording of the deed. This was much more land than many elite

Germans at home could claim. In describing the land, Ernst said every new

farmer could become well to do in only a few years.

Ernst’s letter struck fertile ground back in his

native Oldenburg a country in which the people were generally poor. His letter

describing the opportunities available in Texas created a sensation and was

copied many times. Interest in emigration was especially high in light of the

revolutionary environment and subsequent repression that prevailed in the

German homeland from 1830-1833. By 1833, several German families had responded

with interest to Ernst’s letter. A small stream of immigrants settled near

Ernst’s grant, leading to the establishment of Industry in present day Austin

County. Eventually a whole series of German settlements, Shelby, La Grange,

Cummins, Cat Spring and Bellville sprang up around the area of Ernst’s grant in

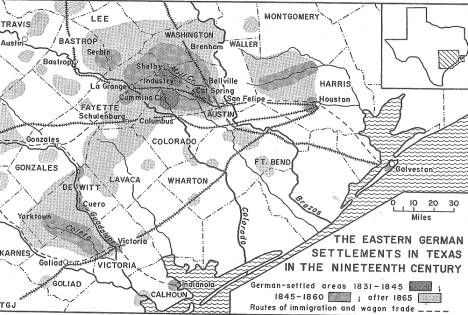

Austin, Fayette and Colorado counties. (see Fig. 3)

Fig. 3 (16, P.

42)

The Republic of Texas

The struggle of Texans for independence from Mexico

tended to slow the flow of immigrants, but in 1841 another important book, Das

Kajuenbuch (The Cabin Book), was published in Germany that further

heightened desires for immigration. Written by Karl Anton Postl, who may have

visited Texas under the assumed name of Charles Sealsfield, this book described

life in Texas in glowing terms and became a best seller throughout Europe.

In the spring of 1842 a most significant event

occurred in Germany with the founding of The Society for the Protection of

German Immigrants in Texas (Verein zum Schutze deutscher Einwanderen en

Texas or Mainzer Adelsverein or Adelsverein or briefly Verein)

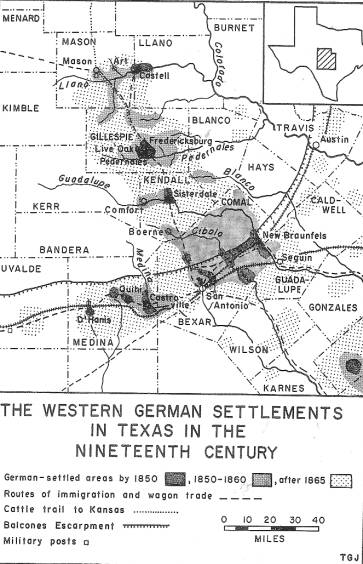

see fig. 4

Fig. 4 (1, P. 92)

Until the founding of the society, no

concerted effort had been made to induce German emigrants to go to Texas. The Verein was a business hoping that

by purchasing lands in Texas and settling them with Germans, they would realize

a profit on their investment as land values increased with development of the

area. The story of the Verein is most interesting but much too long to

describe in detail in this paper. The importance of the society lies in the

fact that through its efforts thousands of Germans were brought to Texas during

the period of its existence (1842 – 1847) and accounted for the settlement of

Texas Hill country. (see fig. 5)

Fig. 5 (16, P.

46)

Harris County

By 1831 Harrisburg, founded in 1823, was a thriving

port. With the creation of the Republic of Texas in 1836, the Mexican village

of Harrisburg became Harrisburg County and finally in 1839 was renamed Harris

County. The boundaries of the new Harris County established in 1839 have

remained the same until present day with the brief exception when Spring Creek

County was created in 1841 only to disappear in 1842.

Several members of Stephen F.

Austin’s first colony, the “Old Three Hundred” were the original settlers of

Harris County. Among these original settlers was John Austin, a distant

relative of Stephen who was granted two leagues in 1824 which would later

become downtown Houston. John Richardson Harris the founder of Harrisburg was

another Austin colonist (see fig. 5 for other early

land grants).

Settlers from Austin’s second colony were concentrated in Northwest Harris County most of them astride Spring Creek. Although titles to these grants were not issued until 1831 most of these colonists had been on the land since the mid 1820’s. Of particular note among these grants is the one granted to Abraham (Abram) Roberts.

Fig. 5 (7, P. 18-19)

Abraham Roberts

probably reached Spring Creek in 1826. A cattleman and businessman, within a

very few years he established the settlement of New Kentucky. By 1831, when he

received title to his grant, this settlement had become a prosperous trading

center. Located near the spot La Salle crossed Spring Creek, New Kentucky was

ideally situated. It was on the old Atascocita Trace, which ran from Monterrey,

Mexico to St. Augustine, FL, and before long it was connected by a road,

connecting Washington on the Brazos with Harrisburg. In the long run however,

New Kentucky was eclipsed by Houston and was abandoned in 1840.

With the coming

of Independence in 1836 the Republic of Texas realized that land must be

offered freely to immigrants in order to compete with pioneering areas in the

United States. In August 1836, two businessmen, John and Augustus Allen,

advertised the founding of a new settlement in Harris County. Houston was

named, of course, for the hero of San Jacinto. Houston would eventually eclipse

both Harrisburg and New Kentucky as the focus of attention in Harris County.

In 1837 a young Frenchman, Claude Nicolas

Pillot, arrived in the new settlement of Houston and immediately moved to the

north to establish his farm on Willow Creek. Eventually the settlement of

Willow would grow in the area of Pillot’s farm. Willow was a thriving community

for many years, but by the mid-1930’s it passed from the scene. The only thing

remaining of this once vibrant settlement is the Willow Creek cemetery located

west of Hooks airport near the FM 2920 bridge over Willow Creek.

In 1838 the Republic opened a land office

in Houston, which spurred a rush of immigration (See fig. 6 for grants under the Republic). In spite of all these land grants

North Harris County remained a very sparsely populated region in the mid

1840’s.

Fig. 6 (25, P.

25)

The Germans of

Harris County

Not all of the German immigrants to Texas followed Ernst and the Verein into the counties west of Harris. Many Germans stopped short of these popular colonies and settled in Harris County. The revolutionary movement of the late 1840’s in Germany produced a wave of immigrants who were to follow the footsteps of those who left in the 1830s and find themselves in Texas. Some of this new wave did proceed to the eastern and western nodes of previous German settlement but many chose Harris County as their new home. This wave of emigrants is often called the “forty-eighters”.

The forty-eighters were fleeing a land torn by social and political upheaval. Searching for free or cheap land and personal freedom, they sailed for America and settled in Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, Missouri and Texas. For the most part they were peasants looking for a better life. This is the group that settled in Harris County. The forty-eighters also included the nobility and well educated, but they tended to settle further to the west in hill country. On some Texas farms a new breed of well-educated immigrant, know as the “Latin Farmer”, settled.

Early German settlers, unlike their Anglo counterparts, put down deep roots. To the German, land was primary. It would become the foundation of an estate that could be passed down through the generations. God-fearing and upright, thrifty and industrious, these German immigrants preserved their ways. They tended to marry primarily within their own community which resulted in intertwined family trees. To this day the descendents of these German settlers are markedly less mobile than the American norm, preferring the warmth of family to the thrill of faraway places. Children grow up, marry and build on land adjoining their parents, commuting to work or earning a living from the land, but staying.” (7, P. 38). The Handbook of Texas declares that the Germans solidly occupied the northwest quadrant of Harris County.

The Communities

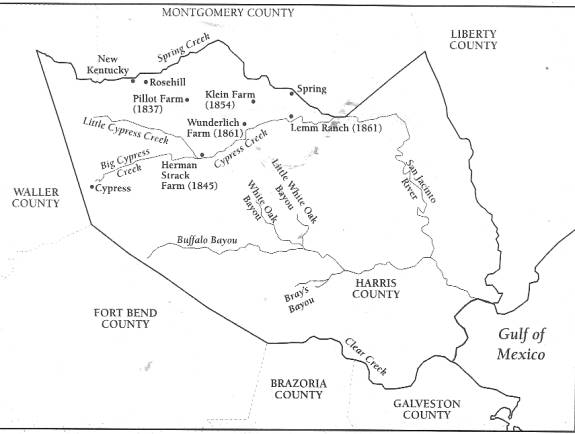

Fig. 7 (25, P. 26)

The Germans of North Harris County began arriving along Cypress and Spring creeks in the 1840’s driven by bad conditions in Germany and drawn by general homesteading grants offered by the new state of Texas. Texas was the first government in the Western Hemisphere to give secure home ownership. Under these rules a homesteader could settle upon vacant public lands provided he improved them, and his property could not be seized for payment of debt. Most of these homesteaders arrived with the forty-eighters and the names are still very much with us today. (7, P. 35)

Perhaps the best way to study the German immigration is to look into the communities formed by these new comers, because it was the community that formed the center of day-to-day immigrant life. The two earliest settlements in north Harris County were Spring and New Kentucky. One is today a thriving tourist town and the other is nonexistent.

Spring

Spring is located alongside IH 45 twenty miles north of Houston. The Spanish were the first Europeans to reach this area in the mid 1740’s. In the 1820’s some of Austin’s colonists settled nearby. At the time of Texas Independence, 1836, the area around current Spring was included in the municipality of Harrisburg. By 1838, William Pierpont, a settler from Connecticut, had established a trading post on Spring Creek that would become the village of Spring.

In the mid 1840’s German immigrants began to settle in the area of Spring Creek to farm the land. In 1846, land near present day Spring sold for 10 to 25 cents per acre, which made the area very attractive to immigrants. Carl Wunsche and William Lemm were early German settlers to the area who took advantage of Texas homesteading grants, settling on land and improving it. The homesteads for these two families were established between 1846 and 1850. Sugar cane and cotton were the main cash crops, but vegetables were also raised.

Prior to the coming of the railroads in the 1870’s Spring was isolated by mud and mire, and the early farmers had to make an overnight wagon trip to take produce to market in Houston. Nearly everyone had a sugar cane patch and brought the crop to the town’s sugar mill for syrup making. The two principal cotton gins in the area were owned by the early German settlers, Charles Wunsche and Antone Mittelstaedt.

With the coming of the railroads beginning in 1871, the town of Spring grew rapidly and eventually became a major switching yard. In the early 1900’s Charles and Dell Wunsche built and ran the Wunsche Brothers Saloon and Hotel (today the Spring Café), which catered to the railroad business. The decline of Spring began in 1923 when the railroads began to move their facilities into Houston. The decline continued through the depression. It was not until the 1970’s that Spring began to recover as a place for harried Houstonians to visit the country, shop and relax.

Most of the landmarks of old Spring and the German presence have disappeared, but one turn of the century landmark remains. In front of Spring High School, on a tiny wooded knoll is the Wunsche family cemetery. This location, hemmed in on all sides by the daily hustle and bustle, is the final resting place for many of those first German immigrants who braved the rigors of the frontier.

New Kentucky

The earliest of the settlements in north Harris County was New Kentucky. It was founded in the late 1820’s by Abram Roberts one of Austin’s second colony settlers. Roberts reached Spring Creek about 1826 and claimed his league of land west of present day Tomball. His grant for this land was not issued until 1831 but when one considers the turbulence going on in Mexico at the time the delay from 1826-31 is not surprising.

By 1831 New Kentucky was already a prosperous trade center being located at the crossroads of the Harrisburg to Washington on the Brazos and San Antonio to Nacogdoches. It was at this crossroads that Sam Houston made the decision to end the “runaway scrape” by standing his ground at San Jacinto, which led to Texas Independence. Although a prosperous trading center by 1831, the lifespan of New Kentucky was to be shortened by the expanding trade competition for the new town of Houston and it was abandoned about 1840. Today the site of New Kentucky is a park and wooded picnic ground 7.8 miles west of Tomball on Hwy 2920.

Rosehill

After New Kentucky one of the earliest communities founded in northern Harris County was Spring Creek Community (present day Rosehill). Founded by P.W. Rose near New Kentucky in 1836, Spring Creek rose in importance as New Kentucky faded away. The first German immigrants to this area were the Theisz family, Johann Henrich, his wife Katherine and four children, three sons Johann Jacob, Henrich and Christian and one daughter Katherina who arrived in Galveston in 1846 from Antwerp. Ship records of the time indicate the Theisz family intention was to proceed to New Braunfels to join the Verein settlement. (38)

It is

important to note that this arrival occurred during the Mexican-American war.

As a result of the war, the U.S. Government had requisitioned all wagon

transportation in the area. Also remember that the Verein declared bankruptcy

in 1847 so they were near insolvency and had abandoned many of the earlier

settlers they had brought to Texas. Hundreds of new arrivals had struck out on

their own from the ports destined for the hill country only to be overcome by

conditions. The winter of 1846 was especially wet and cold which only

complicated the situation. When Johann Henrich inquired about directions for

the trip west he was told “all you have to do is follow the bones and they will

lead you right to New Braunfels.” (29, P. 8)

Concerned for the welfare of his family Johann changed his mind and traveled to the new settlement of Spring Creek. On February 8, 1847 Johann Henrich Theisz, purchased 200 acres of land near the New Kentucky settlement for $1 per acre. It is interesting to note that the deed, which recorded this sale, showed that Theisz used the name Henry instead of Johann Henrich and also spelled his last name Theis. It was not unusual at that time for immigrants to change their name slightly after their arrival in America. Eventually Johann began to use the name John Henry Theis and that completed the Americanization of the name. By the same process the oldest Theis son became Jacob instead of Johann Jacob and the second son Henrich became Henry, Jr.

Soon after the arrival of the Theis family at Spring Creek, other Germans, the Achenbachs, the Burkhardts, the Hampels, the Metzlers, the Scherers and the Winklers began to settle in the area. In the late 1840’s five Strack brothers immigrated to Harris County from Germany. Henry and Johan Jost Strack settled near Spring Creek, but the other three brothers preferred the Cypress Creek area, and we will discuss them later. By 1850 this growing German community was in need of a house of worship. The initial move towards organizing a church was made by the Theis brothers, Jacob and Henry, their sister Katherina’s husband C.W. Winkler and George Scherer. In 1852, this initial group along with other neighbors and friends who lived in the community established the Salem Lutheran Church. In 1853, Jacob Theis, the first son of Henry Theis, was the first child to be baptized in the newly organized church. In 1854, the second child to be baptized was Jacob Theis II, son of Jacob Theis, Sr.

The group initially worshipped in private homes, but finally in 1857 a church building was erected on 4 acres of land donated by C.W. Winkler. In 1868 the Salem Lutheran Church was affiliated with the Missouri Synod. The following year, 1869, George Scherer gave his family cemetery, situated about one mile northeast of the church for the church burial ground. In 1870, the fellowship established a parochial school and built a schoolhouse on adjacent land given by Henry Theis. Many more German families had moved into the area by 1870 including the Hillegeists, the Ruedels, the Brautigams, the Seidels, the Krugs, the Roesels, the Martens, the Fehrles and the Froehlichs. Many of the descendants of these early settlers are still found on the rolls of the church. The church is presently located 2 miles west of Tomball off Hwy 2920 on Lutheran Church Road. The Salem Lutheran Church holds a special place in Texas history, as it is the oldest Lutheran Church in the state.

Not all the German settlers of the Spring Creek community were Lutheran. In 1875 three families, the Beckendorfs, the Oefts and the Schultzes, who had settled west of the settlement, organized The Rosehill United Methodist Church. Later members of the church were the Schauers, the Scholls and the Schwartzes. Located 4.5 miles west of Tomball off Hwy 2920 on Rosehill Church Road the white frame church building, built in 1888 still exists and is the oldest church building in the area still being used for church purposes.

Cypress

Beginning in 1848, German immigrants began to settle along Little Cypress Creek mixing with the Anglo-American settlers who had earlier settled in the area as ranchers. Among the first immigrants were the Zahns and the Bahrs. Some of these early settlers took advantage of Texas homesteading grants, settling on vacant land and improving it, thus eventually taking ownership. Two of these early homesteaders were Augustus Froehlich and Augustus Hillegeist. These first German settlers in the area were later joined by the Quades, the Krahns, the Fenskes, the Juergens and the Matzkes. Rice and dairy farming would eventually become the main occupations of Cypress residents while the trading activity of the community would revolve around the area’s corn cracking mill, the Meyer cotton gin and the sawmill on Grant Road.

The early immigrants to the Cypress area lived the life of true pioneers,

dwelling in primitive huts and experiencing hunger and want in every

conceivable form. These isolated immigrants began to gather, in the open or in

one of their huts, for Sunday worship. In 1853, only a year after the settlers

of Spring Creek (Rosehill) had founded Salem Lutheran church, these staunch

Lutheran Germans of Cypress organized the Saint John Lutheran church and

school.

Over the years St. John underwent several changes. The original building

served the congregation for several years, but by the end of the Civil War the

increase of families emigrating from Germany coupled with the growth of the

original families had rendered the original building inadequate. Soon after the

war a new structure was erected, and the congregation acquired its first full

time pastor in 1872. The second church building was damaged in the 1900

Galveston hurricane requiring extensive rework. In 1908, the St. John

congregation constructed its third church building, but unfortunately in 1915

this building was destroyed by another hurricane. After this hurricane the members

of St. Johns constructed their fourth church building.

By the early 1950s St. John was having a difficult time surviving as a

rural church in a rapidly expanding suburban community, and the congregation

began to make plans for a new house of worship. On 14 May 1961 ground was

broken for the present church located on Spring-Cypress Road near Huffmeister

Road. There is an interesting sidelight to history concerning the St John

church built in 1915. When the current church building was built near Huffmeister

Road the old structure, erected in 1915, was purchased by Windwood Presbyterian

Church and moved to Grant Road at Lakewood Forest Drive where it is still used

on occasion.

The only thing remaining at the original site of St. Johns is the

cemetery. Located off Cypress-Rosehill Road on Lutheran Cemetery Road the

original St. Johns cemetery clearly reflects some of the difficult times these

early German immigrants faced in Cypress. The Cypress area was hit extremely

hard by yellow fever in 1859 and again by smallpox in 1873. Among the graves of

the Zahns, Fenskes and others are many infant graves, which starkly attest to

the difficult life these early settlers of north Harris County faced in making

their homes in a new land.

Neudorf

This German community also dates back to the middle 1800’s. Located

northeast of Cypress, Neudorf was never more than a loose grouping of

farmsteads. Early German settlers in this area included the Schmidts, the

Brautigams, and the Hermanns.

In the 1870’s a split within the Lutheran Church led to a split up of the

St. John’s congregation and the founding of the Trinity Evangelical Lutheran

church in Neudorf. This new church was built on land donated in 1876 by William

and Henerritta Schmidt with the stipulation that it was to be used by “no other

denomination or sect but Lutheran Evangelical.” (31, P. 25) By 1961, Trinity

had become vacant when the congregation reunited with St. John’s in its new

location. Trinity congregants took the chandeliers, alter pieces, organ, hymn

board and baptismal font into their homes. In 1976, the Trinity building was

moved to the Tomball museum area and all the items were returned in excellent

condition and the church restored as it was at its height. The restored Trinity

Church is the now the scene of religious services on special occasions. A

bilingual German and English church service is held here each October and the

church is also available for weddings.

Klein

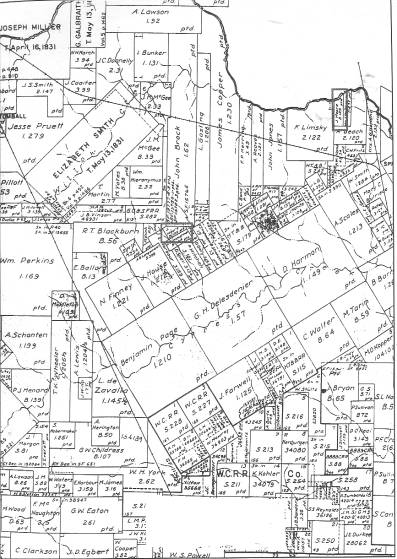

The largest, and probably best known, German community in north Harris County is Klein around Cypress Creek. The first settlers in the area were the brothers Herman, Jakob and Fredrick Strack. Recall that there were five brothers who immigrated, but Henry and Johan Jost Strack chose to settle near the Spring Creek Community. Herman and Jakob purchased land in the Delesdenier survey and Fredrick bought land in the Harmon survey (see Fig. 8 below)

Fig. 8 (7, P.

31)

Fig. 8 (7, P.

31)

The Stracks began cotton farming and expanded over the years. Year by year they continued to purchase land until eventually the Strack Farms included most of the land from Cypress Creek to present day Louetta Road between Stuebner-Airline and Kuykendahl roads. There is an interesting family story concerning Herman and the purchase of one particular 1200 acre piece of land in the Delesdenier survey. As the story goes, Herman had received payment for his cotton crop that year in gold dollars. The land he wished to purchase was for sale at $1 per acre and since he could not carry $1200 in gold pieces to the owners he used a wheelbarrow to do so -- much to the surprise of the sellers.

Over the years the Strack family switched from cotton to raising vegetables for the Houston market. Today Strack Farms is the best-known truck farm of the area and occupies part of Herman’s original acreage.

Adam Klein and his fiancée

Christina Friederika Klink were the keys to the development of Klein community.

Adam Klein was born in Stuttgart,

Germany in 1826. He was a cloth weaver by profession, and as a young man became

involved in the movement for popular reform of the government which swept over

Germany in the 1840's. However, by 1848

the reform movement had been frustrated. Not wishing to serve in the army of

the autocratic German government, Adam Klein went to Switzerland for a time and

then decided to immigrate to America. He persuaded his fiancée to come with him

to this foreign land to begin a new life in America. It is worth noting that

throughout 1852 Adam and Friederika were joined by over 150,000 other Germans

who were also escaping to America.

In late 1851, Adam and Friederika made their

way to Le Havre in France and on 25 November 1851 set sail on the Elizabeth

Hamilton for New Orleans. During their voyage Adam and Friederika were

married by the ship’s captain and so arrived in New Orleans on January 11, 1852

as newlyweds. From New Orleans the Kleins traveled to

Hermann, Missouri, where Friederika's half-brother Matthias had settled. The village of Hermann was settled in 1837 by Germans from Philadelphia

as a place to better preserve their German language and customs than in

Philadelphia.

Once in Hermann, Adam and Friederika were married again. Perhaps they

believed that an American marriage certificate would be more acceptable in

their new land than their word that they had married aboard ship. The Kleins

arrived in Hermann just as the Lutheran church in the settlement was being

split by “free thinkers”. Because they were not in agreement with this radical

sect of the church, the Kleins began to think of moving again.

Gold fever was running high when the Kleins arrived in Hermann and Adam

decided to join a group headed for California. His plan was to find sufficient

gold to finance the purchase of land upon which he and his bride could settle

and begin their family. Adam traveled overland from Independence Missouri to

Hangtown near San Francisco, California. He did discover enough gold for a

stake and decided to return to meet Friederika in New Orleans. In spite of

being robbed twice during his return from California Adam arrived in New Orleans

with his stake and reunited with Friederika in late 1853 or early 1854.

In selecting their new home, the Kleins were influenced by several

factors. The religious split of the Lutherans in Missouri ruled out a return to

Hermann. Events in neighboring Kansas in 1853-54 also discouraged a move into

what would become a war zone. It was Texas, which seemed the most promising to

the Kleins and so they set sail once again from New Orleans bound for

Galveston. Their intentions upon arriving in Texas were to travel inland to the

area of Brenham or Burton, where other Germans had settled, purchase some land

and begin their farm.

Arriving in the fall of 1854 the Kleins realized that with winter rains

coming it was not a good time to travel into the interior. Adam and Friederika

found the German community of Houston welcoming and settled in to await spring.

It was through their association with the Lutheran Church in Houston that the

Kleins most likely learned of the German settlers north of town like the Lemms,

the Stracks and the Theises who were quite well established by 1854. These

German settlers in north Harris County were scattered so thin across the

prairie lands that in most cases it was an hour’s walk or horseback ride from

one settler’s home to another, so land was readily available.

It was in 1854 that Jacob Theis, one of the founders of the Salem

Lutheran Church in the Spring Creek Community (Rosehill), decided to relocate

further east in Harris County. In January of 1854, Jacob purchased 557 acres of

land in what at the time was called Big Cypress, just to the north of Cypress

Creek, for $700.00.

On 15 December 1854, Adam Klein bought bounty land certificate No. 1661

from John and Amanda Coyce, heirs of James Moore, a former soldier in the Army

of the Republic of Texas. Adam paid $106.00 for his land certificate worth 320

acres, 33 cents per acre, and set out to find unclaimed land among the Germans

around Cypress creek north of Houston. They chose to settle on 160 acres north

of Cypress Creek and claimed another 160 acres south of Spring Creek northwest

of the Spring Settlement. Just as in the case of the Stracks, the Kleins over

the years continued to purchase new land as resources became available making

their farm one of the largest in the area.

In 1852, Johann Peter Wunderlich became the first of the Wunderlich family to immigrate to the United States. Later his brother, Jost, and a sister, Marie Katherine, would immigrate to Texas with their families. Peter Wunderlich married Marie Katherine Hofius, and the couple rented land and a room from Jacob Theiss as they began farming. In 1859, Peter began a homestead west of Spring and in 1861 gained title to 577 acres, which became Wunderlich Farm. It was also in 1861 that William Lemm, another German immigrant homesteaded land on Cypress Creek south of Spring, which would become known as the Lemm Ranch.

The German farmers who settled along Cypress Creek developed a specific pattern of land use, which continued for over a hundred years. These farmers tended to purchase property which included Cypress Creek frontage, a portion of the woods which adjoined the creek and as much upland farmland as they could afford. Homes were built well back from the creek, while the wooded areas were used primarily as a resource for firewood, fodder for the numerous sawmills, which sprang up after the Civil War, or shelter and forage for the hogs and cattle, which made up a large portion of the farm stock. (25, P. 29). These farmers became early leaders in market gardening, which had been well developed in Germany.

Religion was very important to the German families who came to Texas. Although there were German immigrants of many faiths, most were Lutheran. In mid-1850s the families along Cypress Creek had no established church so for a while they worshipped in each others homes. Eventually they decided to attend Salem Lutheran Church, which was nearly 15 miles to the northwest near the Spring Creek (Rosehill) Community. Today, of course, we would think nothing of traveling 15 miles to attend church, but in the mid-1850s this was a difficult undertaking.

The journey from Big Cypress (Klein) to Salem Lutheran Church could take a large part of the day to accomplish by wagon. There were no roads so the trip to church was along trails through the prairie. Those traveling would do so on Saturday, and spend Saturday night in the Spring Creek Community area with relatives or friends, in order to be ready for church early Sunday morning.

Edwin “Butch” Theiss explained how he was told by G.W. Brautigam of Tomball “that Jacob Theis traveled by wagon with his family on Saturdays to Rosehill and spent the night with his brother Henry, went to church at Salem on Sunday morning and then traveled back home that afternoon. There were some French people who lived on the route to Tomball (very likely the Pillots) and these people commented to various friends and neighbors that “Jacob Theis must be a very good man because he travels so far every weekend to attend church with his family”. (29, P.11)

After many years of this weekly journey to worship at Salem the members of the developing Klein community decided to build their own church and in 1874 formed the Trinity Lutheran Church. Acquiring 160 acres of railroad land the founding members first constructed a school and worshiped there until the church building was completed in 1882. The names of the founders of Trinity reflect the community leaders of the time: Adam Klein, Jacob Theis, Jost Wunderlich and Henry Kaiser. Other charter members of the congregation included Henry Benfer, Henry Bernhausen, William Lemm and John (Johannes) Brill. Not long after the church was founded the Klink and Strack families joined. The Klink family were cousins of Adam Klein’s wife who had followed her to Texas, and the Stracks, of course, were early settlers to the area.

The Trinity Lutheran Church was and is the heart of the Klein community just as many of the other community Lutheran churches throughout the area. The church services in German not only gave these settlers a common, familiar cultural tie, it also gave spiritual refreshment to these hard working farmers. The church was their refuge, and it was there that all-important events were recorded. Births, marriages and deaths were all matters of church records and today serve as a tremendous source of information for anyone researching the history of this period of Harris County.

Other Communities

Several other small communities with various degrees of German influence make up the North Harris County scene. The first of these is Hufsmith, which began in 1902 when the International and Great Northern Railroad line from Spring to Navasota established a depot stop northeast of the present Tomball. The settlement received its name from the railroad superintendent Frank Hufsmith. Several German Lutherans lived in the Hufsmith area and until 1907 they traveled to Rosehill to Salem Lutheran church for services. In 1907 the citizens of Hufsmith built Zion Lutheran Church, but eventually this congregation moved to Tomball and the schools of the two churches merged,

Stuebner was once a trading center for the area between Willow and Spring

Creeks. The center of this village was a general store operated before the turn

of the century by Adolf Stuebner. The store stood at the northern end of the

present Stuebner-Airline Road. The small crossroads ceased to exist early in

the twentieth century with the growth of Tomball.

The settlement of Kohrville was named around 1880 for Paul Kohrmann, a

German immigrant who ran the post office. This village located near the current

intersection of FM 249 and Spring-Cypress Road was settled by freed slaves

arriving from Alabama in the 1870s.

Louetta was once a small village near the intersection of present day

Louetta and Spring-Cypress Roads. German immigrants never played a large role

in this community. Louetta’s location, however, gave it a trade advantage over

Klein and by 1915 Louetta, not Klein, dominated area maps. By the 1970s however

Louetta had all but ceased to exist while the Klein community retained its

identity.

Bammell centered at the intersection of present day FM 1960 and

Kuykendahl Road was not founded until 1915 by Charles Bammel, a German

Houstonian who moved to the country for his health. One prominent German

resident of Bammel at its founding was Dr. William Ehrhardt a descendent of one

of the early German immigrant families that settled land on the Delesdenier

survey. Dr. Ehrhardt suggested when the post office was established in the

settlement that it be named Bammell, and the name stuck.

Westfield is unique as it is known as the moving community. This

settlement began near today’s Cypress Station on I-45, where a trail crossed

Cypress Creek. The settlement was founded in 1864 by the German immigrant

Herman Tautenhahn who built a general store in this area. By 1873, Tautenhahn

had moved his store to where Bammel Road crosses Hardy to take advantage of the

newly constructed I & G.N. railroad from Houston to Spring. The new

location was known as “Westfield by the railroad” and grew to be a significant

settlement during the early twentieth century.

Westfield was a blend of German and Anglo-American settlers. Mixed with

the Boettchers and Tautenhahns were the non-German Wests, Runnels and Richeys.

Calvin Richey was the son of a frontiersman who had escorted Austin settlers’

wagon trains into Texas. The Richeys were granted land between today’s lower

Medberry Road and I-45 on Richey Road.

After May Richey married Emil F. Strack, their property in the Calvin

Richey survey became prime vegetable-producing land. In 1975 the Texas

Department of Agriculture granted this farm Harris County’s first Family Land

Heritage certificate of honor. This award recognizes a century or more of

continuous family ownership and agricultural production, and was given in the

name “E.F. Strack Farm.” (7, P.79)

Epilogue

German immigration to Texas can be divided into roughly three periods.

The first period begins with the settlement of Friedrich Ernst in 1831 on a

grant of land from the Mexican government within the Austin colony. It was

Ernst who excited interest in immigration that led to the settlement node between the lower Brazos and Colorado Rivers

in Austin, Fayette and Colorado counties. (see Fig. 3 ,P. )

In spite of the interest generated by Ernst, the German population

probably would have remained small had it not been for the second period of

immigration which began in 1842 with the founding of the Verein.

Beginning in 1844, under the supervision of Prince Carl von Solms-Braunfels

and later Baron von Meusebach, it was

the Verein that was responsible for a major influx of Germans to Texas

and the founding of New Braunfels and Fredericksburg in Comal and Gillespie

counties respectively. (see Fig. 5

,P. ) From 1844 to 1846 the Verein

was responsible for bringing 7,380 German immigrants to Texas.(16, P. 45)

In spite of its successful appearance, the Verein was always underfunded

and finally declared bankruptcy in 1847.

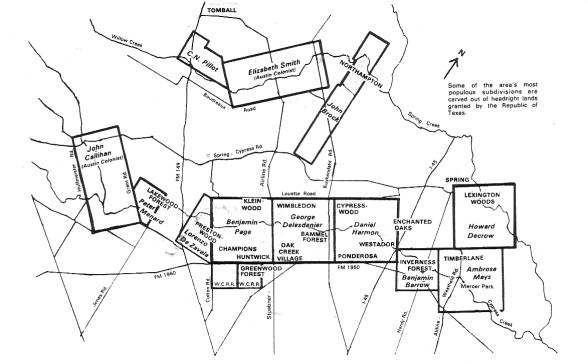

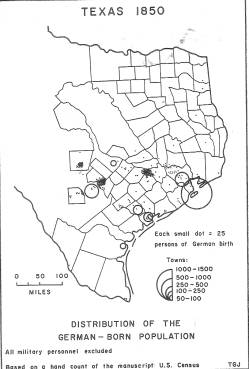

The end of the Verein in

1847 also marked the beginning of the third and final period of German

immigration to Texas. It was in this third period that the influx of immigrants

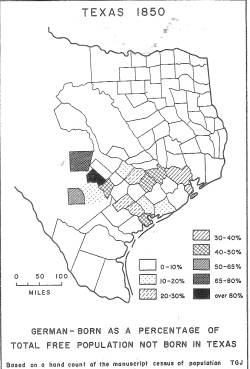

to Harris county began in earnest. Figure 9

below clearly shows three nodes of German settlement in 1850. Also fig.

10 below shows that by 1850 the

percentage of German born in Harris county to be between 30 and 40 per cent.

Clearly the German element in Harris county was significant by 1850 but what is

the impact and significance today

Fig. 9 (16, P. 49) Fig. 10 (16, P. 51)

During my research for this paper I

was invited to a meeting of The North Harris County Chapter of the Texas German

Society. The meeting was held in the Trinity Lutheran School in Klein. The

meeting was attended by over 70 individuals of German descent. Just a casual

look around the room told you that the group was made up of individuals who

represented a cross section of the community at large.

Roaming

the room during the social hour that proceeded the meeting one encountered Stracks,

Theises, Kleins and many of the other names discussed in this paper. Those in

attendance represented every walk of life from businessman to cattle farmer.

The meeting was called to order by the chapter president Roger Wunderlich.

After some initial business, the program of the evening, a presentation of

German folk songs began. It was fascinating to watch as one by one those in

attendance began to tap their feet, clap their hands and smile. The expression

of recognition that spread across the faces is difficult to describe. These

descendants of those long ago immigrants clearly remembered the music and the

words and their minds went drifting back to God-fearing, hardworking family and

loving Grandparents and Great grandparents. They’d brought to Texas a cultural

heritage so strong that it has lasted for generations.

The Germans of North Harris County

are very much with us today not just in the names of places around us but also

in the character of the people we daily pass on the street and with whom we

conduct business. They form the backbone of our modern community and I am

honored to have the opportunity to experience a small part of it.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

BOOKS

1. Biesele, Rudolph Leopold. The History of the

German Settlements in Texas 1831 – 1861. Austin: Eakin Press, 1987.

2. Benjamin, Gilbert Giddings. The Germans in

Texas: A Study in Immigration. New York: D. Appleton, 1909.

3. Bruncken, Ernest. German Political Refugees in

the United States During the Period from 1815-1860. Milwaukee: Strauss,

1904.

4. Charlton, Magdalene. New Kentucky and the Great

Decision. Houston: Spring Creek County Historical Association, 1962.

5. Dresel, Gustav. Houston Journal: Adventures in

North America and Texas 1837 – 1841. Austin: University of Texas Press,

1954.

6. Fehrenbach, T. R. Lone Star: A History of Texas

and the Texans. New York: Collier Books, 1986.

7. Feik, Lorraine et. Al. The Heritage of North

Harris County. Houston: North Harris County Branch American Association of

University Women, 1986.

8. Finck Jr., Arthur L. The Regulated Emigration

of the German Proletariat with Special Reference to Texas. San Antonio:

Trinity University Press, 1978.

9. Fornell, Earl Wesley. The Galveston Era: The

Texas Crescent on the Eve of Secession. Austin: University of Texas Press,

1961.

10. Geue, Chester W. and Ethel H. A new Land

Beckoned: German Immigration to Texas 1844-1847. Baltimore: Genealogical

Publishing Co., 1972

11. Geue, Ethel H. New Homes in a New Land: German

Immigration to Texas 1847-1861. Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co.,

1999.

12. Gish, Theodore and Richard Spuler eds. Eagle

in the New World: German Immigration to Texas and America. College Station:

Texas A&M University Press, 1986.

13. Hagen, Victor von. The Germanic People in

America. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1976.

14. Hatcher, Mattie Austin. The Opening of Texas

to Foreign Settlement, 1801 – 1820. Austin: University of Texas Press,

1927.

15. Huebener, Theodore. The Germans in America.

Philadelphia: Chilton, 1962.

16. Jordan, Terry G. German Seed in Texas Soil:

Immigrant Farmers in Nineteenth Century Texas. Austin: University of Texas

Press, 1975.

17. Justman, Dorothy E. German Colonists and Their

Descendants in Houston. Wichita Falls: Nortex, 1974.

18. Klein, John A. To You …. My Legacy of Love.

Houston: Babcock, 1969.

20. Lich, Glen E. and Dona B. Reeves. German

Culture in Texas: A Free Earth; Essays from 1978 Southwest Symposium.

Boston: Twayne, 1980.

21. Lich, Glen E. The German Texans. San

Antonio: Institute of Texas Cultures, 1981.

22. O’Connor, Richard. The German-Americans, An

Informal History. Boston: Little,Brown, 1968.

23. Quensell, Carl Wilhelm Adolph. From Tyranny to

Texas: A German Pioneer in Harris County. San Antonio: Naylor, 1975.

24. Richardson, Rupert N. et. al. Texas: The Lone

Star State. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall, 2001.

25. Severance, Diana. Deep Roots, Strong Branches:

A History of the Klein Family and the Klein Community, 1840-1940. San

Antonio: Historical Publishing Network, 1999.

26. Smith, Daisy Lauretta. The History of

Harrisburg Texas 1822-1827. Houston: Rankin, 1981.

27. Strack, Rebecca. The Strack Family 1848-1976.

Harris County: 1976.

28. _____________. 150th Anniversary of

the Strack Family in Texas: A Family History Beginning in 1848. Harris

County: 1998.

29. Theiss, Edwin (Butch). The Theis/Theiss Family

History. Spring,TX: 1978.

30. Tiling, Moritz. History of the German Element

in Texas from 1820-1850. Houston: 1913.

31. Upchurch, Lessie. Welcome to Tomball.

Houston: D. Armstrong Co., 1983.

32. Von-Maszewski, W.M. ed. Handbook and Registry

of German-Texan Heritage. German-Texan Heritage Society, 1989.

MAGAZINES, JOURNALS AND NEWSPAPERS

33. Fornell, Earl. “The German Pioneers of Galveston

Island.” American German Review 22 (1956): 15-17.

34. Jordan, Gilbert J. “The German Settlement of

Texas after 1865.” Southwestern Historical Quarterly 73 (1969): 193-212.

35. Shook, Robert W. “German Migration to Texas

1830-1850: Causes and Consequences.” Texana 10 (1972): 226-243.

ELECTRONIC SOURCES

36. The Handbook of Texas Online

http://www.tsha.utexas.edu

37. The Texas Almanac

http://www.texasalmanac.com

38. Galveston, Texas Ship Passenger Lists

http://home.att.net/~wee-monster/galveston.html

39. Harris

County Genealogical Society of Texas

http://www.hcgs.org/

40. Burial Sites of Harris

County

http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.com/~prsmith/key_cem.htm

41. Texas General Land

Office Archives

http://www.glo.state.tx.us/archives/landgrant.html

42. Historic Houston

http://www.houstonhistory.com/

43. The German – Texan

Heritage Society

http://www.gths.net/

44. Klein, Texas Historical

Association

http://www.kleinisd.net/kisd3/farm/kthf.htm

45. Strack Family Cemetary

http://www.groovyghosthunters.com/strack.htm